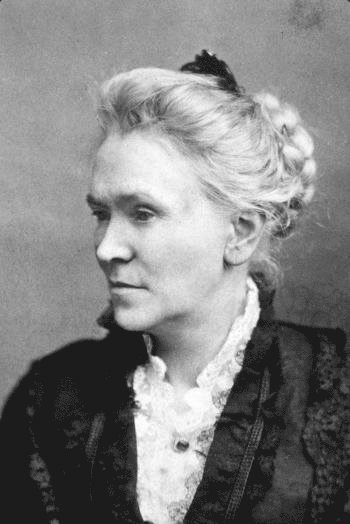

Matilda Joslyn Gage (1826 – 1898)

Matilda Joslyn Gage (Image source, Wikipedia), a suffragist, abolitionist, Native American rights activist, lecturer, and author from Cicero, New York, began her vocation as an activist in 1852 when she spoke at a women’s rights convention in Syracuse, New York. She coedited the first three volumes of the History of Woman Suffrage with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The six-volume publication, written from the perspective of Anthony and Stanton, was part of an effort to establish an official record of the women’s suffrage movement in America. Gage also wrote pro women’s rights essays and pamphlets, often questioning the church’s position on issues she believed made women seem sinful and inferior to men. Gage harbored escaped slaves in her home and supported the rights of Native Americans, speaking out against their cruel and unfair treatment by the US government. In 1890, she organized a group called the Woman’s National Liberal Union, dedicated to challenging the religious mandate of women’s submission to men and halting the encroachment of religion in politics.

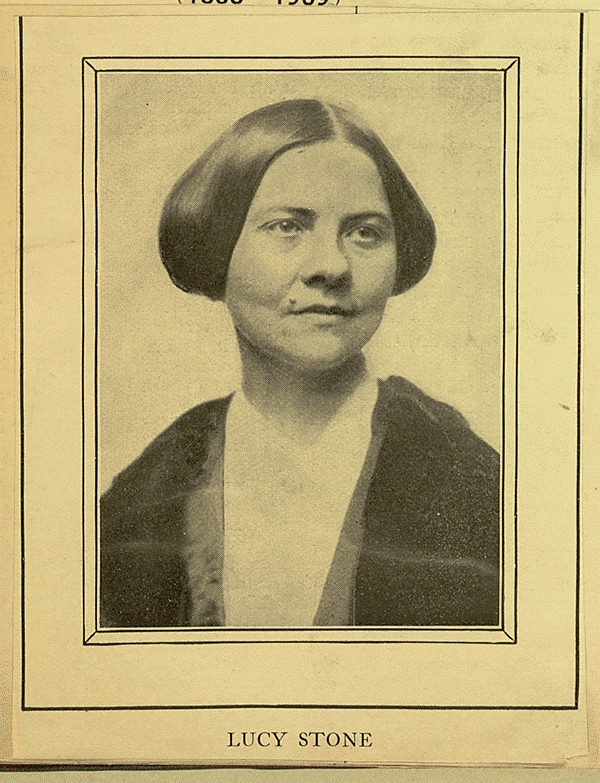

Lucy Stone (1818 – 1893)

Lucy Stone (Image source, Library of Congress) a leading suffragist, abolitionist, newspaper publisher and prominent U.S. orator from West Brookfield, Massachusetts, dedicated her life to battling inequality on all fronts. When she married Henry Browne Blackwell in 1855, she went against tradition for married women by keeping her own last name. Before the Civil War, she wrote and delivered abolitionist speeches for William Lloyd Garrison and his American Anti-Slavery Society, while becoming active in women’s rights and in 1850, organized the Women’s Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts that drew an audience more national in scope. She also worked to pass the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery, and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. In 1869, She broke with Susan B Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton and others over passage of the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution, which granted voting rights to Black men but not to women. Though she wished that the 15th Amendment included suffrage for women, she believed that gaining voting rights for any disenfranchised group helped move America toward equality for all. As a result, Stone and Julia Ward Howe were leaders in the organization of the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) while Anthony and Cady founded the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). However, the two groups did reconcile and merged in 1890 prior to Stone’s death.

Sojourner Truth (1797 – 1883)

Sojourner Truth (Image source, Library of Congress), an abolitionist, evangelist, author, and women’s rights activist, was born into slavery as Isabella Baumfree in Swartekill, New York. After escaping and gaining her freedom in 1826, she sued her former “owner” for custody of her son, Peter after the New York Anti-Slavery Law was passed. Winning her case and regaining custody of her son, she was the first Black woman to sue a white man in a United States court – and win. The family that took her in after her escape and helped with her court case, the Van Wagenens, had a profound effect on Isabella’s spiritual life and she became a fervent Christian. In 1843, with what she believed was God’s urging to go forth and speak the truth, she changed her name to Sojourner Truth and embarked on a lifelong mission to preach the gospel and speak out against slavery and oppression.

Her most famous speech, “Ain’t I a Woman” was given at the 1851 Woman’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. The original transcript printed shortly after the speech by her friend and journalist, Marius Robinson (who reviewed the transcript with Truth prior to publication) differs from the more widely known, embellished version printed 12 years later by suffragist Frances Dana Gage. Regardless of the version, her story of oppression and injustice toward Black women and women in general galvanized abolitionists and suffragists alike.

Like Harriet Tubman, another famous escaped slave, Truth helped recruit Black soldiers during the Civil War and was a guest of President Abraham Lincoln at the White House in October 1864. While in Washington, Truth put her courage and contempt for segregation to work by riding on whites-only streetcars. When the Civil War ended, she worked exhaustively to help find jobs for freed Blacks faced with poverty. She spent her remaining years speaking out against discrimination and in favor of woman’s suffrage, leaving behind a legacy of courage, faith and fighting for human rights.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815 – 1902)

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (Image source, Library of Congress), an author, lecturer, and chief philosopher of the woman’s rights and suffrage movements, from Johnstown, New York began her activism in the abolition movement before shifting her attention to women’s rights, crafting the agenda for woman’s rights that guided the struggle well into the 20th century. While on her honeymoon in London for the World’s Anti-Slavery convention of 1840, she met abolitionist Lucretia Mott. Both were angry about the exclusion of women at the proceedings, so they vowed to call a woman’s rights convention when they returned home.

In 1848, Stanton and Mott planned and held the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York. The Seneca Falls Convention is considered by many to be one of the most significant milestones in the American women’s rights movement. There, a group of women’s rights activists gave speeches declaring the need for women’s political, social, and economic equality to interested listeners over the course of a few days. Most significantly, the activists unveiled a Declaration of Sentiments, modeled after the American Declaration of Independence, which asserted 18 grievances from the inability to control their wages and property or the difficulty in gaining custody in divorce to the lack of the right to vote.

After Seneca Falls, Stanton met Susan B. Anthony in 1851 and the two quickly began collaboration on speeches, articles, and books. During the Civil War both worked jointly to advocate for the 13th Amendment, which ended slavery. After the Civil War she was able to travel more, showcasing her oratory skills and becoming one of the best-known women’s rights activists in the country. However, she and Anthony opposed the 14th and 15th amendments to the US Constitution, which gave voting rights to Black men but did not extend the franchise to women. When asked whether she were “willing to have the colored man enfranchised before the woman,” Stanton answered “no; I would not trust him with all my rights; degraded, oppressed himself, he would be more despotic with the governing power than even our Saxon rulers are.” This position estranged them from other leaders in the movement and resulted in their founding the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) in 1869. Stanton served as NWSA president and wrote for NWSA’s journal The Revolution.

In her later years, she wrote an autobiography, Eighty Years and More, co-authored three volumes of the History of Woman Suffrage (1881-85) with Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage, and published the Woman’s Bible (1895, 1898), in which she urged women to recognize that religious orthodoxy was patriarchal and obstructed their opportunities to achieve autonomy.

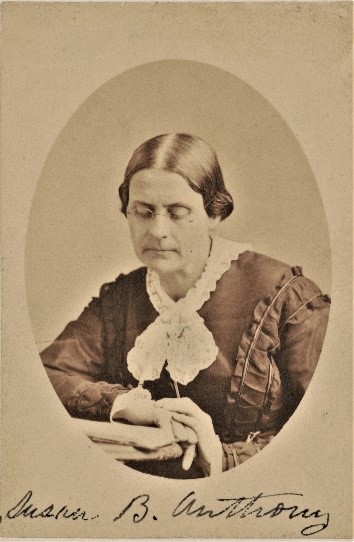

Susan B. Anthony (1820 – 1906)

Susan Brownell Anthony (Image source, Library of Congress), a champion of temperance, abolition, the rights of labor, and equal pay from Adams, Massachusetts became one of the most visible leaders of the women’s suffrage movement. Her father was a Quaker and her mother’s family fought in the Revolution and served in her home state government. As a result, Anthony was inspired by the Quaker belief that everyone was equal under God. After many years of teaching, she met William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass, who were friends of her father. They inspired her to do more to end slavery and she started giving abolition speeches despite the prevailing thought that it was improper for women to give speeches in public.

In 1848, her mother and sister attended the Seneca Falls Women’s Rights Convention, but she did not, meeting Elizabeth Cady Stanton for the first time in 1851. They became fast friends and spent much of the next five decades traveling together and fighting for women’s rights. At times, Anthony risked being arrested for sharing her ideas in public which included emancipation of slaves, promoting women’s right to vote and temperance.

Although ahead of her times in many ways, Anthony, and Stanton like many in their day believed that white women should have priority over Black men when it came to the vote. Neither she nor Stanton supported the 14th and 15th Amendments with Anthony notably stating she would cut off her own right arm before supporting Black men gaining the right to vote before white women. However, many suffragists like Lucy Stone publicly disagreed with Anthony’s stance which led to development of two national suffrage groups being formed.

In 1872, Anthony was arrested for voting. tried and fined $100 for her crime. The publicity generated from this event made many people angry and brought national attention to the suffrage movement. In 1876, she led a protest at the 1876 Centennial of our nation’s independence, giving the “Declaration of Rights” speech written by Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage. She spent the rest of her life giving speeches, gathering thousands of signatures on petitions, and lobbying Congress every year for women and she helped merge the two rival suffragist factions into one, the National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA), serving as president until 1900.

Lucretia Mott (1793 – 1880)

Lucretia Coffin Mott (Image source, Library of Congress), an early feminist activist, minister and abolitionist from Nantucket, Massachusetts, dedicated her life to speaking out against racial and gender injustice through powerful oration. Mott’s Quaker faith stressed equality of all people under God, which guided her belief that slavery was morally wrong, and that men and women should be treated equally. A devoted abolitionist and a fluent, moving speaker, Mott retained her poise before the most hostile crowds. In the 1820s she became a Quaker minister, delivering powerful lectures on the evils of slavery. Over the next several years, she joined or helped form numerous anti-slavery groups. She also began working for women’s rights. At the World Anti-Slavery Convention in 1840, she met and befriended Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Women were not allowed to participate in the convention because of their gender, which frustrated both Mott and Stanton. In 1848, the two women organized the Seneca Falls Convention.

In 1866, during the Eleventh National Woman’s Rights Convention, Stanton, Susan B. Anthony among others organized the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) with Mott serving as president. The following year a schism started when two separate referenda granting suffrage to Blacks and women, respectively was voted down in Kansas. During the Kansas campaign, organization founders Stanton and Anthony accepted the help of a known racist, alienating abolitionist members as well as Lucretia Mott. As a result, AERA later split into two groups, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) which was exclusively female and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). In her later years, Mott was admired by many for her steady commitment to gender and racial equality. She continued her activism and speaking up to the time she died, giving her last address to the Friends’ annual meeting in May 1880.